This post first appears on Law 360 here.

By: Rachel Wolbers and Jonathan Stroud

If you asked your average American about Marshall, Texas, they’d likely picture dusty saloons nestled between long-dormant oil rigs. But for many start-up companies and most patent lawyers, Marshall brings something else to mind: NPEs. Non-practicing entities, or NPEs—pejoratively, trolls—purchase and sue others in search of quick settlements, a practice lucrative enough to land many of them on the NASDAQ and in the Fortune 500, with suits resulting in millions of dollars in profits. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, with streamlined local patent rules, extensive discovery, and quick jury trials, has become their forum of choice. After years of hosting thousands of patent suits (at its peak, roughly half of all such suits in the US), it has gained a well-documented and well-earned reputation. The courthouse features an outdoor ice rink paid for by Samsung, empty office buildings that are home to hundreds of litigious LLCs, and hotels that cater solely to defense attorneys flown in for weeks at a time to defend billion-dollar suits.

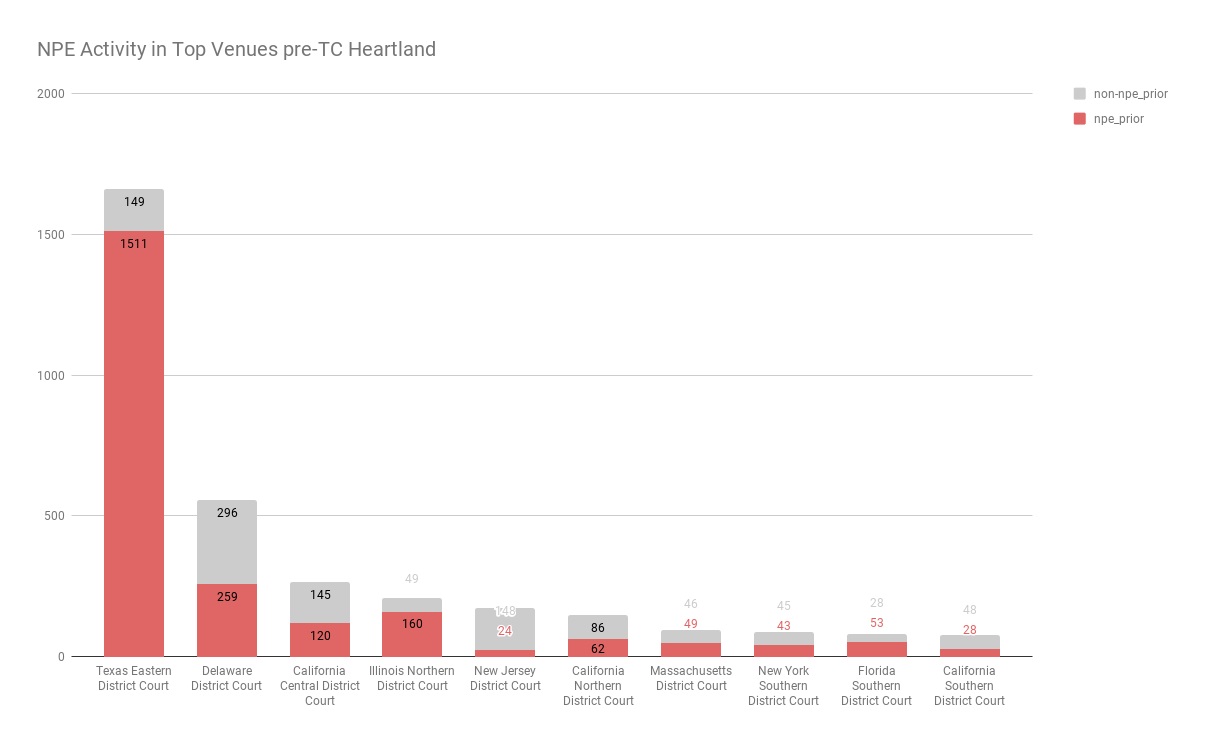

A year after the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Food Group Brands LLC, however, Marshall may be returning to the normalcy of tumbleweeds and prairie, as NPEs who once filed there flock instead to other jurisdictions.

In Heartland, the high court ruled that—for purposes of establishing “residency” for venue in patent cases—domestic corporations are only residents in the state in which they are incorporated, returning to the rule of 30 years ago. This decision was a victory for small startups across the country, many of whom were sued or threatened with suit in the far-flung Eastern District of Texas and forced to settle litigations of little merit.

For three decades, courts took the view that patent holders could bring suit in virtually any federal district court nationwide. NPEs took advantage, filing suit in courts where early trial dates, broad discovery requirements, and a history of large jury verdicts pressured accused infringers to settle quickly (or risk bankruptcy). With complaints costing only $400 to file and counsel working on contingency, NPEs were able to put economic pressure on defendants, whose defense costs routinely topped hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. (Indeed, some personal injury trial lawyers switched to patent law after tort reform defanged some of their more lucrative trial work.) Extorting startups who had just received funding was particularly lucrative, as they typically had cash on hand and no legal team with which to fight back.

The Eastern District of Texas, a rural district where few companies have any physical presence, still plays host to several hundred patent suits annually. At one point, more than 25% of all patent cases in the nation were assigned to a single judge sitting in tiny Marshall—with 45% going to a combination of him and his feeder magistrate judge. That’s out of almost 2,800 sitting federal district court judges, all of whom are eligible to hear patent cases—and many who have never heard one. Why were plaintiffs avoiding your average judge?

In the Eastern District, more than 90% of all patent litigation has been brought by NPEs. This has forced many small and medium entities to pay high settlement fees just to avoid the significant cost and uncertainty of the fast, uncertain litigation in that far-flung venue—even when the patents may be bunk, the claims may be abusive, or the party may not infringe.

The Supreme Court’s decision began to stem that tide and has in the past year led to a slightly more balanced caseload nationwide, though now just three districts still represent almost half of all suits. It marked a major milestone in the battle against NPE litigation; we are now starting to see the results.

Indeed, the tiny District of Delaware, with its two active sitting district court judges (and at least two vacancies yet to fill), now plays host to a bigger slice of the pie. Time will tell if litigants even out their venue choices still further; patent pilot program judges across the US stand ready to take their cases. It is worth noting that startups and small businesses have historically accounted for over 55 percent of patent troll defendants; for them, TC Heartland ensured that they can litigate in jurisdictions where they can travel easily, where their witnesses are likely located, and where they already have a presence. Effectively, the ruling allows large companies with national presences to still be sued across the country (only fair as a cost of doing business in a district), but prevents start-ups from being dragged into states they have no connection with. It’s no surprise venue reform had been a top priority for startups and the tech community for years.

But the fight against NPEs is far from over. While some cases have shifted from Texas to Delaware, the overall volume hasn’t decreased all that much, and still remains far higher than prior to 2005, when patent litigation began to increase in earnest.

As the data shows, TC Heartland may indeed be considered a watershed case in addressing the extreme forum selection in patent law, and to some extent the threat of NPE litigation abuse faced by startups across the country. And there other problems need fixing to ensure that our patent system works as it was intend—to promote the progress of science and the useful arts rather than incentivize profiteers.

First, innovators large and small rely on patents to protect their intellectual property, but allowing low-quality patents to flood the system enables NPEs to file abusive lawsuits. The office could make policy changes that restrict the sheer volume of patents issued each year—more than 300,000. Additionally, with the average patent lawsuit costing upwards of a million dollars, policymakers should consider sensible reforms, like customer-suit provisions, to bring these costs down. Reforms that have been enacted have done this remarkably well; according to the self-reported AIPLA Biannual Economic Survey, the cost of litigation has decreased across categories by almost half since the AIA was passed:

Startups and innovators must remain engaged with policymakers in Congress and at the United States Patent and Trademark Office to promote patent quality and sensible litigation reforms. NPEs use the patent system as a clever means of extortion, but doing so undermines the entire system. TC Heartland brought some sense to a wildly imbalanced system, but it will take more than a few “vacant” signs in Marshall, Texas to protect our innovators.