This piece was originally published in Morning Consult.

After almost five years of legal volleying, the U.S. Supreme Court finally issued a decision in the highly anticipated Apple v. Samsung design patent case late last year. On Tuesday, Dec. 5, the court delivered a unanimous decision in favor of Samsung, finding that damages for design patent infringement may be limited to revenues attributable to a component of an article of manufacture rather than profits from the entire article. While this is an important victory for startups and innovators—from global corporations to inventors toiling in garages—courts must still work to provide the guidance and clarity necessary to prevent bad actors from abusing the patent system to the detriment of innovation. And they have a new opportunity to do so: On Feb. 7, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit took a significant step in that direction by remanding the Apple v. Samsung case to the Northern District of California court.

Before we get into why this development is so important, a little background on Apple v. Samsung. As many are aware, the case centered on the “smartphone wars” between Apple and Samsung, which have been entangled in a long-standing dispute over patent rights for their respective mobile devices. The crux of the current dispute relates to “design patents,” which are intellectual property rights covering the appearance of functional objects. Apple argues that it owns design patents that cover the “iconic” look of the iPhone. Apple tried to recover damages for Samsung’s alleged copying of the physical characteristics of iPhone by bringing a claim for trade dress infringement but lost when the judges held that the trade dress claims were unjustified and that the physical characteristics on which the claims were based were “unprotectable.” Undeterred, Apple sued Samsung for design patent infringement. Apple initially won on its claim that Samsung infringed Apple’s design patents (including a patent for a rectangular electronic device with rounded corners), and a jury awarded more than $1 billion to Apple—the total profits from Samsung’s infringing smartphones.

That a jury awarded Apple such massive damages for infringing patents on things like “a home button” and “a grid of on-screen icons” led to an outcry from the tech community, including many big tech companies and other industry stakeholders concerned about the broader implications the decision would have on the tech sector if infringements of such minimally important design features could lead to the disgorgement of all profits from a particular device. In December 2015, Samsung successfully petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case and examine whether the jury’s award of Samsung’s total profits for the infringing smartphones was appropriate in light of the fact that fact that the patents in question only covered a few specific design features of the product. Arguments in the case were heard by the court last October.

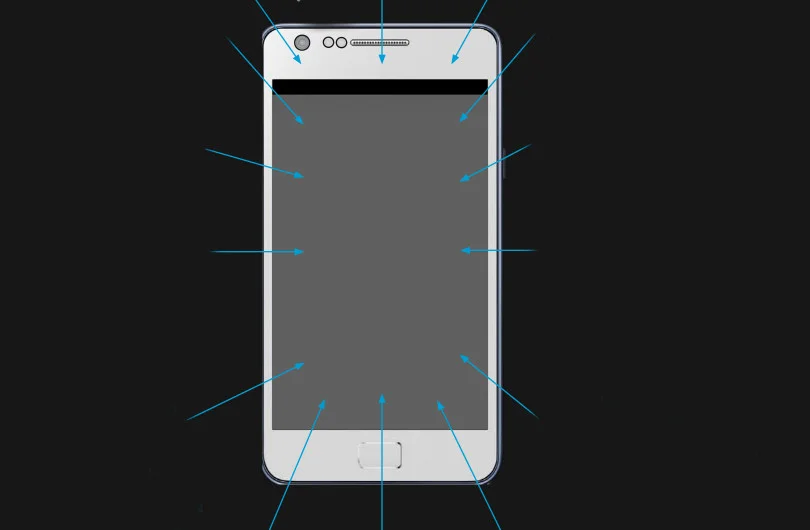

Prior to the court’s decision, lower courts affixed total dollar value to a single holder of a single allegedly infringing design feature—even if the feature is not the overall design of the product. While total profits awards may arguably have been more appropriate in an age when devices were less complex and the design of the object constituted a significant portion of its value, the complexity of modern devices renders total profits awards for design patent infringement particularly illogical. As this graphic illustrates, devices like the ones over which the smartphone wars were waged contain a dizzying number of components from a variety of different contributors, all of which combine to give the object its value. Consider Bluetooth 3.0—a technology incorporating the contributions of more than 30,000 patent holders, including 200 universities—or the micro SD removable memory storage card, whose more than 800 patent holders make up the SD Card Association. Imagine what would happen if patent trolls could assert a single design patent to claim the total value of these contributions and innovations, regardless of the design patent’s actual impact on the product’s total value.

The dangerous implications of allowing design patent holders to claim total profits damages for infringements are obvious, and the rationale of a total profits regime is weak. Unless consumers are buying phones principally because of their patented rounded rectangle corners, total profits awards produce windfall profits for design patent holders well beyond their actual economic value. Perversely, these unjustified damages awards hinder rather than promote innovation, directly undermining the fundamental purpose of patent law and emboldening patent trolls.

A parallel case between Apple and Samsung currently before the U.S Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit further brings into question the logic of total profits for design patent infringement. In this case, Apple is claiming that one of its utility patents, “slide-to-unlock,” was critical driver of the iPhone’s success, and therefore an injunction should be issued for infringing on their patents. However, Apple made the same argument about “critical” importance of its design patents. Does Apple believe that every one of its patents is worthy of an injunction or total profits award?

As patent law developed, it’s no surprise that lawmakers failed to predict that we would one day carry around miniature computers integrating more than 250,000 individual patents in our pockets. Fortunately, the Supreme Court, which had not reviewed a design patent case in more than 120 years, has restored some sanity to the patent regime and brought patent law better in line with the realities of our technology-driven economy by reversing the lower court’s ruling. Now that the Federal Circuit has remanded the case to the Northern District of California, Judge Lucy Koh should grant a new trial to determine the article of manufacture that bears the design and what profits are attributable to only those patents. Failure to do so may perpetuate the lack of judicial clarity which brought the case to the Supreme Court and risk putting patent trolls ahead of the true innovators growing America’s digital economy.